March 3, 2008

New Sheriff in Town

New Sheriff in Town

By Laura Gater

For The Record

Vol. 20 No. 5 P. 14

To avoid any financial pain that may be derived from the Recovery Audit Contractor program, hospitals need to become familiar with the process that will be in effect in every state by 2010.

As most hospital administrators can attest, Medicare will go to great lengths to detect and recover any overpayments made to facilities, physicians, and suppliers.

The latest effort is the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program, whose mission is to reduce Medicare’s improper payments through the detection and collection of overpayments, the identification of underpayments, and the implementation of actions that will prevent future improper payments, as ordered by section 306 of the Medicare Modernization Act.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) began a three-year demonstration project in March 2005 that focused on California, Florida, and New York—states with the highest Medicare expenditures. The Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006 mandates that the CMS implement RAC programs nationally no later than January 1, 2010. Programs will be implemented on a rolling basis beginning this year.

RACs, which are private companies with proprietary search engines of Medicare and Medicaid rules, subject all claims to their proprietary automated review software algorithms to identify overpayments and underpayments. Data mining is followed by a request for repayment or a medical records request for auditing. Under the program, RACs are paid a percentage of the payment errors that they identify.

“I do not believe that it is useful to characterize the RAC demonstration as hiring bounty hunters with data-mining authority to identify Medicare overpayments,” says Timothy P. Blanchard of McDermott Will & Emery LLP and a member of the American Academy of Professional Coders’ (AAPC) Legal Advisory Board. “Indeed, technically, the RACs are now, although not originally, compensated for finding payment errors—both overpayments and underpayments. Rather, the demonstration has established that the CMS can retain audit contractors on a contingent fee basis, thereby avoiding administrative expenditures that are not effective at the recovery of overpayments.”

The demonstration project has been a success, according to Nancy Hirschl, president of Hirschl & Associates, a coding compliance and revenue integrity consulting firm. “The RAC program will become an ongoing part of everyday work at hospitals. It is time consuming and resource intensive, but most hospitals have not added staff to handle the extra work. It takes hospitals a considerable amount of time to review RAC findings, identify whether or not they agree with RAC findings, and compose and submit their rebuttals,” she says.

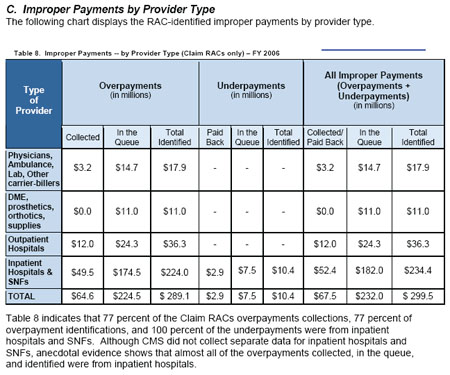

According to the CMS RAC Status Report, the pilot project collected $68.6 million in overpayments and $232 million on the queue (in the collection or repayment process but not yet returned by or to the provider), and received $2.9 million in underpayments for a total of $303.5 million in improper payments. These totals include both claim RACs and Medicare Secondary Payer RACs; Table 1 reflects claim RACs only.

How It Works

The RAC review program consists of three tiers: Part A — Diagnosis-related group (DRG) reviews where medical records are requested and reviewed; Part A and Part B — extrapolated payment errors where a medical record review is not required and transpose clauses are based on claims data; and Part B — durable medical equipment, drugs, and renal dialysis where medical records are requested and reviewed.

Using DRG data-mining software programs, RACs analyze historical MedPAR data and identify accounts that possess the greatest potential for DRG overpayment error. However, random account selection is not part of the program. Training, education, and auditing are the cornerstones of the RAC demonstration and will continue to provide the foundation as it is rolled out nationwide.

“Significant overpayment dollars have been identified and recovered, and significant issues have been identified, which should guide future policy refinement and provider education. Whether problematic policy areas will be refined to facilitate correct claims and sufficient documentation remains to be seen, however,” says Blanchard. “The fact that a majority of providers was found to have had problems in connection with a particular rule or set of program instructions does not make payment errors OK but should prompt a review of the problematic provisions to determine what makes them so difficult for providers to implement, document, or understand properly.”

RAC Targets

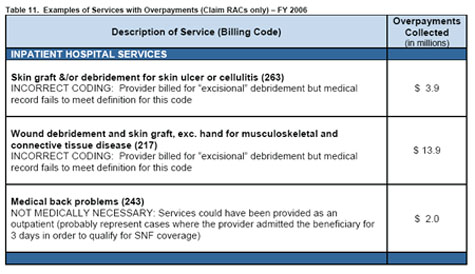

RACs are initially focusing on DRG payment errors, reviewing claims data as far back as 2001. In the demonstration, some of the top DRG requests seen in California were 416 concerning septicemia age greater than 17; 217 concerning wound debridements and skin grafts, except hand, for musculoskeletal and connective tissues; 468 about extensive operating room procedures unrelated to principal diagnosis; 124 about circulatory disorders except acute myocardial infarction, with cardiac catheterization and complex diagnosis; and 475 about respiratory system diagnoses with ventilator support.

“Their best success has resulted from incorrectly coded services, noncovered [local coverage determination (LCD)] services, violations of Medicare Secondary Payor rules, and duplicate services,” says Julie E. Chicoine, JD, RN, CPC, the integrity program director at the Ohio State University Medical Center and an AAPC Legal Advisory Board member.

The RAC Status Report noted that the most DRG changes were made in the following areas: 416 septicemia, age greater than 17; 397 coagulation disorders; and 217 wound debridements and skin grafts, except hand with debridement.

“Incorrect assignment of ICD-9-CM code 86.22, excisional debridement, resulted in the highest financial overpayment impact for the RACs in California, Florida, and New York,” says Hirschl. “Coding and documentation issues also involving sepsis and respiratory failure accounted for a high volume of DRG RAC changes.”

According to Gloryanne Bryant, RHIA, CCS, senior director of corporate coding and HIM compliance with Catholic Healthcare West, there is the potential for miscoding several inpatient DRGs, including single complications and comorbidities DRGs, sepsis, and one-day stays and inpatient rehabilitation. One-day stays are being scrutinized to be sure that the patient met criteria for one-day stay acute care, a physician order for admit to acute care was obtained, and the admission was warranted for an acute level of care. Meanwhile, inpatient rehab records are being reviewed to ensure that the level of care was appropriate for the patient’s condition and the patient met criteria for an inpatient rehab setting.

“RACs have an incentive by contingent compensation to identify areas most likely to have payment errors. Accordingly, providers should expect them to look for cases that are easy to establish and to continue to work those issues until they are no longer fruitful sources of compensation before moving on to more difficult cases,” says Blanchard. “It follows that the RACs may also need to investigate a broader range of claims situations to maintain a similar or expanding error identification rate going forward as providers improve in areas in which repayments have been recovered and as CMS and its contractors improve applicable interpretations and explanations, as the case may be. The targets you have identified reflect areas in which, one, documentation is difficult or may be considered not clear enough for payment purposes even if adequate for treatment and other purposes and/or, two, areas in which current payment policy is simply flawed and should be changed. I think that the best example of the latter is the policy regarding one-day stays.”

Outpatient services are being treated differently, notes Hirschl, in that medical records are not being reviewed manually but rather are being automatically processed for billing/charge errors. CPT coding and billing of blood transfusions, speech therapy, and high-cost drugs are being checked for billing and charge description master errors.

According to Chicoine, RACs perform two types of reviews: the automated review and the complex (medical records) review. “No medical records are involved in the automated review,” she says. “RAC conducts data mining and identifies claims that contain an overpayment, ie, payment does not comport with LCD, [national coverage determinators], statute, regulation, etc. This typically involves a drill down on certain DRGs. The provider receives a letter demanding repayment. The provider bears the burden of proving that the RAC is in error and has 30 days to dispute the overpayment determination.” A typical example includes repayments for outpatient evaluation and management (E&M) charges that are not reasonable and necessary as they are in violation of global surgery bills and E&M services on outpatient hospital claims. Inpatients are DRGs identified through data mining.

In the case of complex review, RAC will identify overpayments through data mining and then send the provider a letter requesting medical records for an identified number of overpaid claims to validate overpayment.

Implementation Strategies

Hospitals need to accept the fact that RAC is a reality and prepare themselves for the long term, says Hirschl. “Identify which department will hold the responsibility for tracking and trending outcomes,” she says.

RAC is an ongoing process, and institutions should expect the volume of demand letters to increase dramatically as the CMS and RACs fine-tune operational processes, says Chicoine. “Hospital and physician providers will need to consider operational issues such as staff to devote time and resources to photocopying charts, reviewing the RAC’s audit responses, and keeping track of what the provider believes merits appeal and what the RAC rebuts,” she explains. “Providers also need to consider forming an operational team, including members from finance, medical records, compliance, case management, and others, to manage the RAC activity, including tracking all requests for production of records and payments made, overseeing recovery and assembly of information requested, reviewing records prior to submission for any errors, retaining copies of documents submitted for future reference, and tracking appeals and outcomes.”

St. Vincent’s Medical Center in Jacksonville, Fla., has hired additional staff to handle RAC requests. “We receive large-volume chart requests from [the RAC] with a 45-day response time to get them copied and sent,” says Lisa Porter, RHIA, CCS, the facility’s reimbursement and coding compliance manager. “Our state was one of the first selected. It was new territory for the RACs and new territory for us. The best plan is to have one primary contact person for RAC—we chose our compliance officer—who will coordinate all RAC correspondence and ensure deadlines are met. I review the RAC DRG denials and appeal as appropriate. I ensure the coding is updated and rebilled for the DRG changes.”

Chicoine advises hospitals to strategically consider proactively retaining their own RAC to conduct data mining on their behalf to identify overpayments and recover underpayments, which may offset RAC overpayment recovery.

“Hospitals should establish a team to handle RAC medical record requests, which during the demonstration have been extremely onerous and will still be a burden on a provider not withstanding the implementation of limits on the volume of records requested by the RACs going forward based on the experience gained in the demonstration,” explains Blanchard. “Providers can reduce the likelihood of RAC-identified overpayments by improving the quality of their medical records and should focus initially on areas that have been identified as sources of significant payment errors in the demonstration. This applies to all providers but may be particularly important for providers that have utilization profiles that depart from the norm, since a perfectly appropriate practice may appear aberrant to the data miner.”

Bryant says hospitals should form a RAC task force, meet regularly to discuss strategies, and establish a RAC toolkit on their internal Web site that would serve as a centralized resource. This online toolkit should contain patterns and trends, an update of RAC findings, and include links to RAC articles and strategies.

Response, Rebuttal, and Appeal Strategies

According to Bryant, once the hospital agrees with the overpayment decision, the RAC will process and deduct the money from future CMS payments. If the hospital disagrees with the RAC’s findings on a particular case, it has to submit evidence to support its stance. A determination will then be made within 120 days, and the hospital can ask for a redetermination by a qualified RAC, which will take place within 180 days. If the hospital still disagrees with the decision, it can request a hearing with an administrative law judge, which has to take place within 60 days. After that, the hospital can request a review by the Medicare Administrative Contractor, which will take place within 60 days. The final level of appeal is a judicial review by a U.S. District Court, which must be heard within 60 days of the contractor decision.

“Providers can appeal identified overpayments,” says Chicoine. “The appeal goes to the fiscal intermediary or the new Medicare Administrative Contractor that processed the claim. The RAC is then given an opportunity to rebut the provider’s appeal. If the provider loses the appeal, the provider also pays interest on the claim during the appeal process. Likewise, CMS must pay interest when the appeal is favorable to the provider. The RAC’s strength in this process appears to play on the quality of hospital and/or physician documentation.”

Providers must respond within 45 days of receipt of a letter and include a photocopy of the entire medical record in question. The RAC has 60 days to review the provided information, verify that an overpayment exists, notify the provider of the overpayment, and demand that repayment be made. Providers may request an extension of time but must do so within the 45-day time frame.

This can be problematic in that letters don’t always go to the right individuals or offices within a large institution, according to Chicoine. For example, they may be sent to quality review or midlevel financial departments, which can result in a delay in response. Additionally, RAC activity is not a one-time event for any provider. The volume of letters to any given provider can range anywhere from one or two to 100 per week. The volume of letters requiring medical records can be burdensome and range from 10 per week to 100 in one month.

It is important for providers to remember that the normal appeal process is available for RAC-identified overpayments. “Given the potentially high volume of overpayment determinations once the RAC audit is implemented in an area, affected providers must plan to pursue appropriate appeals in a timely and effective manner,” says Blanchard. “To date, CMS believes that the RAC findings have been largely accurate, given only modest appeal volume and reversal rate on such appeals. CMS has acknowledged instances of inconsistent application of coverage policy in some areas and has in at least one case suspended RAC activity pending further program review of the claims in question. Part of the explanation for the modest appeal volume to date may be the level of provider awareness and the availability of resources to pursue appeals. Providers should not simply repay RAC-identified overpayments without evaluating carefully whether to concede appeal rights regarding the claims, documentation, and payment in question.”

Hospitals should feel comfortable defending their data when they have documentation and information to support their decision and should feel empowered to do so, says Hirschl.

The Future

Providers should note the favorable changes that the CMS is incorporating into the RAC program based on the lessons learned in the demonstration.

“The changes include requiring each RAC to retain a medical director, limiting the ‘look back’ period to a maximum of 36 months, limits on the volume of medical records that may be requested, requiring RACs to refund compensation earned on recoveries that are ultimately reversed at any level of appeal, and requiring earlier consultation with CMS regarding potential errors before initiating full-scale audits and recoveries,” explains Blanchard. “Although some level of error will always exist in any system of claims payment, it looks like the only way to get rid of the RACs will be for providers to make then unprofitable by eliminating the errors that can efficiently be identified by the available data analysis and review procedures. After all, that is what should happen eventually if the RACs are doing their job, which is identifying the source of significant payment errors, and the providers and CMS respond appropriately to the identified issues by adjusting billing and documentation procedures and addressing problematic policies and policy statements, respectively.”

— Laura Gater’s medical and business trade articles have been published in Healthcare Traveler, Radiology Today, Corrections Forum, Credit Union BUSINESS, and other national and online publications.