March  2019

2019

HIM Challenges — The PDPM: Prepare and Prevail

By Leah Killian-Smith, NHA, HSE, RHIA, CIMT

For The Record

Vol. 31 No. 3 P. 28

In 1987, the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act, better known as OBRA, was passed. It was the first major revision to the Requirements of Participation for nursing homes since 1965. The overarching principle was that nursing homes were expected to provide care and services to “attain and maintain each resident’s highest practicable physical, mental, and psychosocial well-being.”

This language, which has been carried forward into today’s regulations, is the basis for nursing home standards of care.

Fast-forward to 2016 and the regulations for nursing homes changed again, representing the second largest changes since 1991. This time it was a major overhaul that came in three phases. Phase 1 was implemented November of 2016, followed by Phase 2 in November 2017. Phase 3 is scheduled to take effect this November.

The thought was that phasing in the 800 pages of regulations would ease the burden on nursing homes across the country. Nevertheless, there are varying opinions about the burden of regulations being placed on nursing homes.

On July 31, 2018, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) released the Prospective Payment System and Consolidated Billing for Skilled Nursing Facilities (SNFs) Final Rule for fiscal year 2019, which included patient-driven payment model (PDPM) language. Published in the Federal Register on August 8, the final rule is expected to result in an estimated increase of $820 million in aggregate payments to SNFs during fiscal year 2019.

SNF Value-Based Purchasing

The value-based purchasing program will reduce payments to nursing homes by 2% up front. If a nursing home does well on its rehospitalization measures, it has an opportunity to reclaim a portion of that money.

The measures score, which includes achievement and performance scores, compares each nursing home with all others nationally during a specific period. In fiscal year 2020, the baseline data will be derived from 2017 figures while the performance data will originate from 2019 data. Therefore, providers must realize that their performance today will be used to calculate rates in the next two years.

The industry is struggling to stay on top of all the recent changes, making it difficult for organizations to be thinking two years out.

If a facility has 25 or fewer stays during the performance period, an adjustment will be made. Situations where a disaster has occurred have an extraordinary exception policy to compensate for the losses.

SNF Quality Reporting Program

The Minimum Data Set (MDS) is a collection assessment used to determine a resident’s level of care and payment rate. Measures reported from the MDS assessment for the quality reporting program include section GG: functional abilities, I0020: primary medical condition, J2000: major surgery within the last 100 days prior to admission, section M: skin conditions, and section N: drug regimen review.

Some providers discovered too late that if they dashed (-) the boxes in section GG (except for discharge goals), an additional 2% reduction in the annual payment rate is likely.

Leadership is encouraged to review weekly MDS submission reports to ensure they are being submitted on time and accurately. Note that an error message listed as 3879 is a payment reduction warning.

Quality measures are derived from MDS data and claims-based information.

The Cost of Funding SNFs

Besides the regulatory changes, it was determined that there were significant issues with the current payment system for long term care. The costs and provision of therapy are based on minutes of therapy but do not consider the residents’ goals and preferences.

The current case-mix model, RUGs-IV, was implemented on October 10, 2010, along with a new MDS (MDS-3.0). Many providers expressed frustration that as soon as they figured out how to optimize their payments, the rules changed, forcing them to start over again and to learn a new payment system.

ICD-10-CM Coding for Long Term Care

Because PDPM will focus more on individual resident conditions to determine base rates and case-mix indices, accurate coding is more important than ever.

From experience teaching ICD-10 coding for postacute care across the country, it is evident that few organizations have coders with training of any kind. Typically, the person coding the medical record searches in the EMR diagnosis listing and chooses the code that “looks like it’s right.” Opening a coding book is the exception to the rule.

Training and time constraints both are factors in accurate coding. Many nursing homes still have coding books from 2015 when ICD-10 was first implemented because leadership does not understand the importance of purchasing a new manual every year to keep abreast of coding changes.

Typically, coders in long term care do not have any training or, at best, one to three days’ worth. Long term care coders do not necessarily need to be credentialed professional coders, but adequate training is imperative for billing purposes, gathering statistics, and clinical competence.

It’s been reported that more than 70% of nursing homes utilize MDS coordinators to code. Staff members coding in long term care include nurses, medication aides, nursing assistants, relocated workers (worker’s compensation individuals who cannot perform certain physical tasks), and admissions staff.

For nurses, the reasoning is that because they must complete Section I of the MDS, they are the most logical candidates to handle coding. Section I data collection includes the category of the clinical condition along with the diagnoses. Acute care coding differs from long term care in that it requires coding for episodes of illness or injury. Long term care requires coding throughout the resident’s stay as therapy begins and ends, as conditions resolve, and as new diagnoses are provided by the health practitioner.

PDPM

According to CMS, the PDPM will be beneficial because of its ability to do the following:

• focus on the resident instead of the volume of services provided;

• decrease administrative tasks for providers; and

• improve payments for underserved residents without increasing total Medicare payments.

PDPM includes case-mix adjusted components that are specific to the resident data collected. The five components are as follows:

• therapy services (physical, occupational, and speech);

• nontherapy ancillary services; and

• nursing.

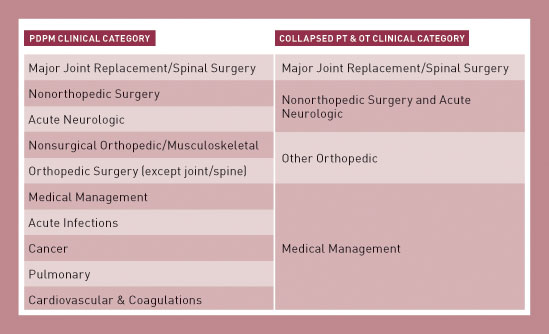

The rate, which is variable, is calculated based on the categories listed in the following table.

The calculations begin with a therapy base rate multiplied by the case mix index for that discipline. That total is multiplied by a variable per diem rate, which adjusts the per diem rate over time. Under RUGs-IV, the rate is funneled into a single volume-driven rate. To the contrary, PDPM considers the specific characteristics of the resident related to his or her goals.

Therapy minutes will no longer be the basis for therapy payments. Therapy will be separated out under PDPM, not in one bucket. For residents who have complex medical issues, the payments are supposed to be more accurate under PDPM.

For years, nursing homes have focused on therapy-intensive referrals from hospitals. In the future, medically complex patients will be more of a focus. This is designed to expand reimbursement options for skilled nursing services.

Essentially, PDPM evens the playing field among postacute care providers, including nursing homes, home health, long term care hospitals, and inpatient rehabilitation centers.

The four major systems to review and ensure competency are ICD-10-CM, restorative nursing, MDS accuracy, and quality documentation. Providers that educate and prepare staff do not need to worry about the implementation of PDPM.

The fear of the unknown can be paralyzing for providers. Smart leaders will observe, audit, and integrate current standards of care and services to ensure their organization is ready for PDPM.

— Leah Killian-Smith, NHA, HSE, RHIA, CIMT, is director of quality and government services at Pathway Health, Inc, and author of an ICD-10 coding for long term care training course. She is responsible for supporting quality assurance efforts, managing relationships with government agencies, education, training, and assistance with the regulatory compliance initiatives in postacute care.