September  2016

2016

Brain Power

By Sandra Nunn, MA, RHIA, CHP

For The Record

Vol. 28 No. 9 P. 22

Health care organizations that develop intellectual capital through communities of practice stand to create a winning learning environment.

Since the publication of Hubert Saint-Onge and Debra Wallace's Leveraging Communities of Practice for Strategic Advantage in 2003, the idea of using communities of practice (CoPs) to enhance the development of intellectual capital both for business and community purposes has spread into such unlikely places as the US military. Learners still gain expertise from formal education and training ("book learning"), but more organizations and communities need the tacit, hands-on knowledge they can acquire through the individuals and teams within their business's networks.

"Communities of practice which connect people in conversation around complex topics are perfectly poised to do this and provide a place for advancing the speed of learning and transfer of intellectual capital," says Harold K. Davis, a community facilitator at the United States Army Cyber Center of Excellence and a part-time instructor at Kent State University.

CoPs not only enhance organizational capabilities but also add to an individual's skills toolkit and network of resources. The development of these networks leads to a more rapid dissemination of knowledge related to a business's strategic messaging. In turn, the speed at which knowledge can be exchanged is accelerated.

In the groundbreaking book The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization, Peter Senge remarks that "organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning how to learn together" lead to innovation and competitive advantage.

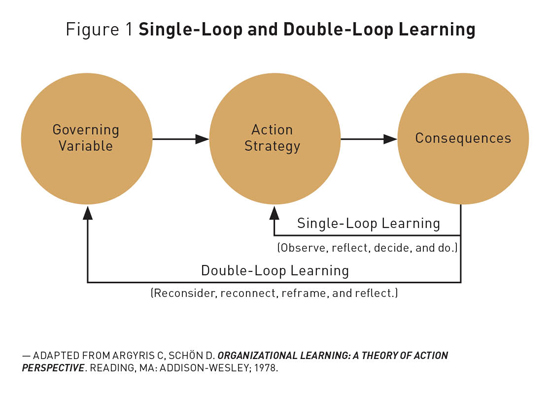

Business theorists Chris Argyris, MSc, PhD, and Donald Schön, PhD, perhaps best known for creating the single-loop/double-loop learning dichotomy (see Figure 1), believe that organizational learning is actually problem solving, which involves what CoPs call "productive inquiry," ie, asking questions that can lead to new ideas, new rules, and new processes.

In Leveraging Communities of Practice for Strategic Advantage, Saint-Onge and Wallace state that "communities of practice in a strategic context are a new expression of an age-old structure that fosters collaboration and learning. The concepts are fairly straightforward—give people with a like interest some time, attention, and resources so that they can collectively solve problems encountered in the workplace. But to meet the accelerated pace of change in the knowledge era, organizations will need to leverage communities to increase capabilities with greater speed and use them with greater agility. Our key thesis is that organizations will need to provide more than casual support in order to maximize the value produced in communities."

The provision behind this statement is that a prerequisite for successful organizational CoPs involves strong organizational support. This can be difficult because true CoPs are open ended and more informal than the usual taskforces characteristic of hierarchically organized institutions.

In his 2001 book Managing Intellectual Capital: Organizational, Strategic, and Policy Dimensions, David J. Teece, PhD, suggests that "the essence of the firm in the new economy is its ability to create, transfer, assemble, integrate, protect, and exploit knowledge assets." He builds a case for business capabilities, indicating that the way an organization "senses and seizes opportunities" to reconfigure its knowledge assets reflects its dynamic business capabilities.

Intellectual capital can be thought of from an economic perspective in that it helps organizations assess the full range of its assets—tacit and explicit, visible and invisible—that are available to achieve business goals. The current trend in health care organizations is to create information asset inventories that sum up databases, applications, and occasionally human assets in terms of knowledge workers as part of the inventory. However, forward-thinking organizations are adding knowledge assets such as innovative ideas and processes to their inventory of information capital.

From a management perspective, businesses both consume and produce intellectual capital. As a result, they can create a competitive advantage to survive in an information economy.

What Is a CoP?

With years of HIM and IT experience, I was confident I would breeze through my CoP course this spring as part of my Information Architecture and Knowledge Management master's program. After all, I have spent years as a member of one or more CoPs under the AHIMA umbrella.

Nevertheless, I was surprised to discover that communities are defined in a certain way and that many of my professional groups are not communities at all. For example, the AHIMA Standards Task Force is just that—a taskforce designed to produce certain information objects and then to dissolve once targets are met.

In the 2002 book Cultivating Communities of Practice, authors Etienne Wenger, PhD, Richard McDermott, PhD, and William Snyder, PhD, state that "communities of practice are groups of people who share a concern, a set of problems, or a passion about a topic, and who deepen their knowledge and expertise in this area by interacting on an ongoing basis." The nature of communities is actually long-term and not characterized by the turnover of communities established by organizational hierarchies. Members in valid CoPs do not turn over on a scheduled time basis nor do they turn over when certain information objects—such as the development of a policy or a procedure—are completed. Indeed, communities are groups that share a level of expertise and wish to share that expertise over long periods of time with newer arrivals entering that field.

In "A Case Study of a Longstanding Online Community of Practice Involving Critical Care and Advanced Practice Nurses," Noriko Hara, PhD, and Khe Foon Hew, PhD, examined to what extent nurse participation in an online LISTSERV constituted a CoP and to what extent the nurses employed electronic media to communicate with one another. The authors found six critical success factors that were foundational to the long-term success of the CoP, which was founded in 1993 and currently has 1,044 members. Those factors, which favor the successful propagation and success of any CoP, are the following:

• self-selected members;

• the need to ask questions and validate one's practice with others that share a similar working situation;

• the need to keep up with the field's current knowledge and best practices;

• a noncompetitive environment;

• the availability of an asynchronous online communication medium; and

• the availability of an effective LISTSERV moderator or facilitator.

In Communities of Practice: Learning, Meaning and Identity, Wenger notes that learning takes place through practice and "membership implies a minimum level of knowledge of that domain—a shared competence that distinguishes members from other people." The advanced practice nurses' community is characterized by an atmosphere of apprenticeship. There are seasoned experts, some even known nationally, who welcome newcomers and provide responses to their queries. Nursing professionals self-select to join the group but are required to have the necessary position and expertise.

There is also a knowledgeable facilitator who screens members and establishes a bar for the level of queries to be considered worthy of the group's attention. Like many successful CoPs, there is a noncompetitive environment in which newcomers can spend time as observers to get their footing prior to jumping in with queries or offering their own suggestions for good practice. Also, the CoP, via the facilitator and other more expert members, posts the latest best practices to keep members engaged in the community's value.

Facilitators provide full access to productive inquiries, including frequently asked questions and instructions on how to create and post new knowledge. A capable facilitator also manages the archival of inquiries and responses. This involves developing and sustaining mechanisms for meaningful, nonlinear threaded dialogues that do not become unwieldy and out of date.

Successful CoPs feature an agreement among participants on conventions such as the format and length of productive inquiries, capitalization and punctuation specifications, and "netiquette" rules to control the appropriateness of inquiries and responses. Facilitators must monitor the length and quality of inquiries and limit the posting of advertising, recruiting materials, and requests for materials to complete work or school assignments. The facilitator also manages the level of expertise of the membership to ensure that informed resources are available to members. In addition, the facilitator may determine and maintain the technological infrastructure to support the CoP in a virtual environment or collaborate with IT to manage technical support.

Community Types

Whether it is being part of a knitting circle or sharing knowledge about collecting archeological artifacts, participation in communities is a common experience. These informal communities, which are typically self-forming and organic, don't have an organizational sponsor, but still may develop individual capabilities and codify knowledge.

In contrast, supported communities are most common in organizations. Their mission is to develop intellectual capital and competence for a given business capability. They can be self-joining, member-invited, or manager-suggested, but they all have one or more managers as sponsors who ensure that the community develops business capabilities linked to organizational goals and strategies.

Organizations may also boast structured CoPs, which are sponsored by a business unit or upper management. Because they are not spontaneous or self-forming, these CoPs rely on strong organizational support to carry out more formal, defined tasks.

Regardless of community type, they all contribute to the strategic value of the organization at some level. They connect people with people and people with knowledge, promote innovation, facilitate participation in value-creating networks, help members develop skills, and encourage collaboration across the organization.

Building the Framework

CoPs are born when individuals, organizations, or both develop a sense that more can be accomplished through shared knowledge or when initiatives, such as information governance, demand the exchange of ideas and the development of intellectual capital around a new topic.

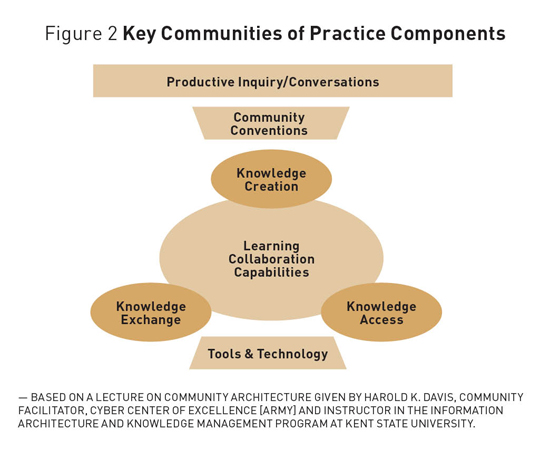

Collaboration and teamwork are the new mantras of modern organizations. Even organizations thought of as highly hierarchical—the military, for example—are getting on board with the concept to benefit from the innovation and intellectual capital creation characteristic of good CoPs. (Figure 2 demonstrates the key components required to construct the CoP architecture.)

The core of CoP architecture, whether for a physical or virtual environment, is the development of a means for members to initiate conversations through the posting of inquiries to other members. Organizations that place a priority on collaborative development create an atmosphere for productive inquiries. In other words, there must be an attitude that training and education need not come strictly from "official" sources, but can be developed by CoP members for one another and eventually for the entire organization. CoPs initiate change, and learning organizations will have change management approaches and technologies already in place.

CoP conventions, including norms, guidelines, routines, and a collaborative culture, must be present. These conventions address governance, membership selection criteria, codes of conduct, participation guidelines (member activity requirements), roles and responsibilities, sharing, and creation expectations and protocols.

The third component of CoP architecture involves relational capabilities in which the CoP synthesizes existing knowledge to create new knowledge, and shares the findings through collaboration and learning.

Lastly, there must be enabling tools and technologies, which encompass everything from discussion boards and SharePoint documents to physical and virtual libraries. These tools should "facilitate rich conversations, encourage participation, support knowledge access, and provide flexibility in the community structure," Davis says.

Establishment and Growth

Once the CoP is established—which may occur through a project management initiative—work must be done to build the membership. This entails building relationships among members, enticing them to engage with one another rather than strictly with the facilitator. To meet this goal, members must have access to knowledge about each other to discover potential relationships and professional commonalities.

Davis advocates the 1-9-90 participation model in which 1% of the CoP members perform the majority of the community support, 9% are active members (contribute to discussions, add content to the site, and work to improve the practice of the profession), and 90% are peripheral lurkers new to the CoP experience who wish to learn and grow professionally prior to contributing.

Once a community has its conventions in place and developed a means of interacting with the selected facilitator, it must acclimate members to the virtual space and begin to suggest activities and events. Growth depends on creating value for members, the CoP itself, and the organization.

CoP Assessment

In an era when data and metrics are being emphasized, it's important to develop measurements to assess the CoP's worth. Is it delivering value to its members and to organizational supporters?

An established CoP should have feedback channels in place to provide members a means to communicate both positive and negative experiences. For example, members must be able to comment on the ability to find answers to inquiries that help resolve research or work-related issues. They also must have the means to point out perceived shortcomings in the CoP that, if mitigated, would add value to the community.

Minimal technical support can produce numerical metrics such as total membership, changes in membership levels, discussions occurring by specific topic, page reviews, and documents downloaded.

Finally, a successful CoP must consider connecting with a larger cohort in its domain. For example, an HIM community within an organization could consider linking up with AHIMA. With the plethora of social media technologies in place today, community growth and value delivery is seemingly limitless.

— Sandra Nunn, MA, RHIA, CHP, is a contributing editor at For The Record and principal of KAMC Consulting in Albuquerque, New Mexico.