October  2019

2019

HIPAA Challenges: Balancing Policy and Technology

By Lesley Berkeyheiser

For The Record

Vol. 31 No. 9 P. 6

When implementing privacy and security controls within a health care environment, there’s a constant need to determine the appropriate balance between the policy expectations (how the workforce is held accountable to comply with the rules) and how technology is employed to facilitate or promote the desired outcome (the appropriate use/disclosure of information). Whenever one or the other (policy or technology) advances, situations such as the recent one involving Google occur.

As reported by The New York Times in June, a data sharing partnership between Google and the University of Chicago Medical Center resulted in a violation of patients’ privacy rights, according to a class action lawsuit filed by a former patient. The search engine giant and the medical center formed the alliance to “unlock information trapped in electronic health records and improve predictive analysis in medicine.”

Technological advances in the past 20 years or so have catapulted patient care to new levels. With that in mind, it’s important to note that the landscape has changed significantly from when HIPAA was enacted in 1996. Case in point: When health care organizations were initially trying to grasp HIPAA’s concepts, the routine use of e-mail and cellphones was just beginning.

Today, health care organizations are only scratching the surface with artificial intelligence (AI) in an effort to develop predictive analytics, a process that requires machines to learn how to identify medical conditions by analyzing a vast array of health records.

However, with these potential gains in treatment strategies come privacy concerns. For example, the Google–University of Chicago lawsuit alleges that date stamps and doctor’s notes were not removed from the records shared with Google. If patient data were not properly deidentified and their exposure was not authorized by the patients, the defendants would have committed a HIPAA violation.

The issue is further complicated by Google’s ability to combine the data from the health records with information it already stores, such as location data from smartphones through apps such as Waze, to identify patients.

At this point, it is unclear whether the University of Chicago Medical Center failed to remove all patient identifiers or if this effort allows for the sharing of some data in the form of a limited data set as part of conducting research.

Both Google and the medical center deny any wrongdoing.

Moving Forward

Technology continues to evolve and improve. Through the analysis and collection of information contained within EHRs, AI can help improve health care quality and lower costs. However, those processes must adhere to privacy standards, specifically the HIPAA regulations that provide the definitions and restrictions of how protected health information (PHI) is handled.

It’s important to note that HIPAA’s overall purpose is to allow PHI to be used and disclosed to support health care services for the purposes of treatment, payment, and health care operations. Strictly speaking, the law’s privacy regulations set forth the rules regarding what data can be used and by whom, while the security portion defines the “how.”

HIPAA’s Security Rule was promulgated to maintain data confidentiality and protect integrity while making the data available for health care purposes. This has been the case since early 2005, but it has been and always will be agnostic with respect to choice of technology. In other words, the requirements and regulations have not changed, but the technology has advanced.

Many other specific disclosures are set forth in great detail within the privacy regulations (examples include but are not limited to disclosures for law enforcement and responses to court orders and subpoenas). However, if not specifically called out in the regulations as permitted or required for disclosure, a valid HIPAA authorization must be obtained from the individual before any PHI can be used or disclosed. HIPAA also provides specific rules about obtaining authorizations, including how, why, and when.

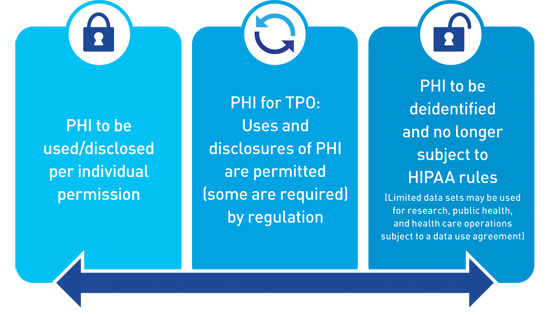

The only way to use or disclose PHI and not obtain an authorization (if outside the permitted and required disclosures) is to deidentify the data. As illustrated in the image below, it is helpful to think of the general principles of data sharing under HIPAA as a spectrum in which the control of PHI rests with the individual who owns it on one end. If a valid authorization is obtained, data may be shared outside of the basic treatment, payment, and operations.

On the opposite end of the spectrum is deidentification. Information that is deidentified is no longer subject to the policies and procedures that limit the use and disclosure of PHI. The rule states that all identifiers (which fall under 18 categories) must be removed.

The Office for Civil Rights has provided additional guidance that can be found on the Health and Human Services website.

It should be noted that HIPAA also allows for a limited data set of records (a subset of PHI from which direct identifiers have been removed, but that contain certain potentially identifiable information). A limited data set may only be used for the provision of specific research, public health, and health care operations.

How to Proceed

To prevent a controversy such as the one embroiling Google and the University of Chicago Medical Center, it’s imperative that organizations understand the regulations. Both deidentification and the use of limited data sets may be invaluable tools in the quest to achieve the desired business need. Keep in mind, however, that the requirements are prescriptive and must be followed specifically.

In the Google case, it is unclear whether deidentification or a shared limited data set were utilized. Another possibility is that deidentification was unsuccessful. Perhaps the statistician failed to recognize that Google could use other forms of technology (such as Waze or Google Maps) to identify individuals. Or maybe not all required identifiers were removed and prepared in accordance with the regulations.

If information is properly deidentified, it is no longer subject to federal HIPAA privacy regulations. While not required, as a best practice measure it is recommended that organizations create a written agreement outlining the limitations for the use of the deidentified information.

Lessons Learned

No matter the outcome of the lawsuit, the situation offers a learning opportunity for health care organizations on how to properly share patient data in accordance with HIPAA regulations. The following are helpful hints on how to avoid trouble with the law:

• Make time to review the HIPAA basics. Many organizations seem to use the term “deidentification” loosely. Be careful to train workforce members on the importance of using the HIPAA privacy definition. For some purposes, such as research and operations, a subset of PHI or a limited data set can meet the business need to share the data and still provide the protection necessary to comply with the regulations.

• Know your data. Understand how your workforce members handle sensitive information in your environment. This includes using it internally and disclosing it to others.

• Ensure your privacy and security compliance program allows for technological advancement. Stay on top of current trends. For example, AI, cloud-based storage, and app development are a few of the latest innovations in the quest to exchange data more efficiently. If such technologies are implemented, ongoing risk analysis and evolving policies and procedures should reflect the level of acceptable risk tolerance and the recommended methods for safeguarding data.

• Maintain compliance. Safeguarding data is a dynamic process. What worked yesterday may not be as strong today. Ensure your organization places privacy, security, and cybersecurity compliance high on its priority list. Stay current by reviewing lawsuit determinations, corrective actions from breach situations, and frequently asked questions on the Office for Civil Rights website.

The progression of technology and compliance with regulations often mesh like oil and water. However, the result of these challenges will help the health care industry determine the right balance between the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of PHI with the ability to embrace new technologies and products.

As the Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT moves toward the promulgation of rules for the 21st Century Cures Act and patient data become interoperable through the Trusted Exchange Framework, more changes will be taking place. As a result, achieving that same old sweet spot of balance between the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of health data and new technology will once again be strained.

— Lesley Berkeyheiser, a reviewer for the Electronic Healthcare Network Accreditation Commission and HITRUST practitioner at The Clayton Group, has served the health care industry for decades to facilitate the secure implementation of privacy and security safeguards. She may be contacted at LBerkeyheiser@EHNAC.org.